Clark Kent's glasses by Ferruccio Giromini

Joe Sacco's cartoon journalism is a genuine blessing, not just because of all its intrinsic merits, but also because it clearly demonstrates that the language of comics in general continues to be rich, independent, full of surprises, with trumps up its sleeve that can be found nowhere else. There are, at least in his case, two basic reason for this. The first is closely linked to journalism. Compared with print or television colleagues, a comic journalist obviously takes much more time to complete his stories. Only at first glance is this requirement a hindrance, since it allows him more time to reflect, to check his sources more thoroughly, to reach a considered opinion, and probably all in all to observe more objectively the state of affairs he is dealing with. His readers can relate to this, also because (and here we have the reason linked to comics) readers of comics bring more than the average amount of attention and above all more involvement to what they read/look at – in other words, they always put something of themselves into it. This filling the space between one drawing and the next with your own thoughts and feelings is after all a typical aspect, the rule even, when reading comics.

So in our feverish, hysterically breathless, syncopated times, Joe Sacco's work is absolutely original: a eulogy of slowness. What is more, it works on two levels. On one level we have the slowness of the author: freed from the tyranny of having to produce materials in “real time”, he has time to look around him, to get people to tell him stories, to soak up atmospheres thoroughly in order to be able to reproduce them better in his pages. On the other there is the slowness of the reader: forced to enter the reporter's mind through his eyes, he listens to the evidence while scrutinizing the speaker's face, absorbs not only superficial “facts” but goes right to the heart of situations. It is a little like moving across the divide between news and history while being clearly aware of the difference, aware that it's a completely different metabolic process. Sacco's viewpoint of course is and will remain partisan; but then, not even the best history book will ever be totally unbiased.

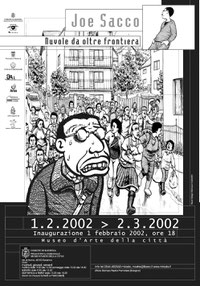

In any case, Joe Sacco does his job very well indeed – perhaps because he was probably the first to do things this way. He practically invented the use of cartoon reportage, especially from dramatic situations on the brink of war. Few imitate him. The long knight of cartoon journalism, he fully accepts his responsibilities and rides on alone. We might add heroically.

Of course, like any good war correspondent, he puts himself in the front line. Like Ernie Pyle in real life and Oesterheld and Pratt's Ernie Pyke in the imagination, he is center-stage. He is, at one and the same time, witness, author and character. And in this way he is also a perfect expression of the universe of comics. His character, his role, his method are certainly rooted in great journalists like John Reed and Hunter S. Thompson, but, as he himself admits, as a youngster he learned enthusiastically from the British Fleetway war comics and from Bob Kanigher and Joe Kubert's Stg. Rock albums. And going back still further to his Australian childhood, the World War II stories he heard from his pals' fathers, who came from a wide variety of European countries, were extremely important.

Born in Malta, he spent his childhood first in Australia and later in the United Sates in Los Angeles and Portland, went back again to Malta, then on to Germany. Continual contact with ever different, multilingual, hybrid communities has influenced his world view as much as his political and aesthetic choices. In today's Olympus of international comics, alongside one Maltese stateless person – a romantic seafarer with an earring – and one bespectacled journalist who at the drop of a hat becomes a heroic defender of the weak, Joe Sacco has his place too – and long may he remain there.